Statue Project

- Sponsors and Friends, Thank You!

- Dedication Ceremony, Stanton, KY

- More pictures from the dedication

- Letter from President Jimmy Carter

- Dedication Speech by Fontaine Banks

- Preparing the Statue Site

- The Artwork by Raymond Graf

- Clay City Times Article April 20, 2007

- House-Senate Joint Resolution 84

- Prestonsburg Statue Dedication

- First Annual Bert T. Combs Symposium

- Clay City Times Symposium Article

Sara Walter Combs, Chief Judge of KY Court of Appeals, and Project Director Joe Bowen unveil Governor Bert T. Combs Statue in Stanton, KY Photo: Tim Webb- www.timwebbphotography.com

Dedication and unveiling of the statues honoring Governor Bert T. Combs

April 20, 2007

in Stanton and Prestonsburg, KY.

Both Statues are now available for viewing. Please come by and enjoy a wonderful tribute to a truly great Kentucky Statesman.

Out of sincere respect and admiration for former Governor Bert T. Combs, the people of Kentucky have commissioned two life-sized bronze statues to honor his memory and legacy. The first statue is located in Stanton, KY, just a few hundred yards from the Bert T. Combs Mountain Parkway. The second is located at the Courthouse in Prestonsburg, KY.

Following are two articles by Joe Bowen that appeared in "The Kentucky Explorer Magazine." These articles are published by permission.

Part I Of Two Parts:

Bert T. Combs Had Progressive Administration As Governor

Education And Highways Were His Top Priorities For Kentucky

By Joe Bowen - 2004

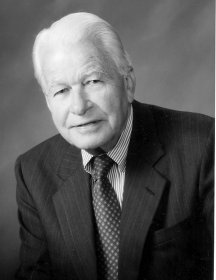

Bert T. Combs, 1911-1991

Governor of Kentucky 1959 - 1963

When Bert T. Combs ran for governor in 1955 my father, Bill Bowen,

was a staunch supporter, along with most of our friends and relatives.

Combs lost. Then in 1959 he ran again and became the governor that

brought Kentucky, kicking and screaming, into the modern age. For most

of us in Eastern Kentucky, Combs became an icon, a governor of the

working class people.

It was back then that I became interested in Bert T. Combs. Now as a

61-year-old man I have read hundreds of news clippings, official papers,

and two books about Combs' life. He lived on his farm, Fern Hill, only a

few miles from my home in Powell County, and I regret that I did not get

to know him personally.

Bert T. Combs was born on August 13, 1911, on Beech Creek in Clay

County, in the heart of the Eastern Kentucky mountains. Combs was reared

in a poor family of seven children. His dad, Stephen Combs, ran a

sawmill and farmed to make ends meet. His mom, Martha Jones Combs, was a

schoolteacher. She was young Bert’s inspiration to get a good education.

Bert attended Oneida Baptist Institute, and at age 15 was

valedictorian at Clay County High School. He later graduated first in

his class at Cumberland College. He saved his money from a job with the

Kentucky Highway Department so he could attend the University of

Kentucky Law School. There he graduated second in his class in 1937.

Bert first practiced law in Manchester. After realizing that family

and friends expected him to work for free he moved to Prestonsburg.

While living in Prestonsburg, in September 1942, he enlisted in the U.

S. Army as a private. In early 1945, as a lieutenant, he went overseas

to serve on General Douglas McArthur’s staff. He later became chief of

the War Crimes Department Investigating Section in the Philippine

Islands. For his work in apprehending and prosecuting Japanese war

criminals, Captain Combs received the Bronze Star and was decorated by

the Philippine government.

After the war Combs came back to

practice law in Prestonsburg. In

1951 Governor Weatherby appointed Combs to the Kentucky Court of

Appeals, the highest court in the state at the time. When the office

came up for election Combs beat the former and popular governor, Simeon

Willis, for the office.

In 1954 Governor Wetherby and Governor

Clements handpicked Combs to

run against A. B. Happy Chandler for governor. Combs, with his “mountain

twang” and sincere and sometimes shy demeanor was no match to the

backslapping, baby kissing, natural campaigner, “Happy.” So he lost.

Not much was seen of Combs for the next four years. But Combs was not

idle. When election time for the governor’s office rolled around in

1959, Combs was ready. He knew what he wanted to do for Kentucky. Wilson

Wyatt, a highly-respected attorney from Louisville, planned to run for

governor on the Democrat ticket, also. It was suggested that Combs run

as Wyatt’s running mate, and together they could beat “Happy” Chandler’s

man, Harry Lee Waterfield. After a poll showed that Wyatt couldn’t beat

“Happy’s” man, but Combs could, the two men agreed that Combs would run

for governor and Wyatt would run for lieutenant governor. They won the

primary and beat their Republican opponent in the fall election by the

largest margin ever, 280,000 votes. Combs became the first governor from

Eastern Kentucky since 1927.

Bert T. Combs, governor of Kentucky during 1959-63, greeted political figures of Powell County. Edwin Rose, left, former county judge of Powell County; and Billy Joe Martin, county judge of Powell County at the time of this photograph, united with Governor Combs with a joint handshake. Barely visible in the background is Forest Meadows, future county judge of Powell County. (Photo courtesy of Floyd Anderson, 70 Allen Drive, Stanton, KY 40380.)

Combs, as the cliché goes, “hit the ground running.” His number one

priority was to advance Kentucky’s educational system. Speaking to the

Frankfort Rotary Club, September 11, 1963, Combs said, “When we entered

the 1960s our nation was at the summit of world leadership. It was

obvious that if Kentuckians were to play a significant role in that

leadership, we must be awakened to our responsibilities and

opportunities.

“We gave our attention first to education,

because every survey of

public opinion indicated that education of children held first place in

the hearts of Kentuckians. I think most Kentuckians feel that if there

is a single key which can unlock the door to a brighter future that key

is education.”

To advance education and accomplish other visions

that Combs had for

Kentucky would take money. He recommended a three percent sales tax,

which a small portion would go to pay a veterans’ bonus. With the sales

tax he gave all Kentucky veterans a bonus and pumped an additional

$267,870,792 into public education from 1960 to 1964. This was the key

Governor Combs applied to the lock.

During Combs’ four years

teachers’ salaries nearly doubled, helping

to keep good teachers in Kentucky. Five hundred one-room schools were

eliminated. Thirty new high schools and 102 new elementary schools were

built, and additions were made to 87 high schools and 181 elementary

schools. This created 4,653 new classrooms in Kentucky.

During Combs’

years as governor Kentucky’s support for higher

education increased by 115%. He started the Community College System and

Kentucky Educational Television (KET) that both serve our citizens so

well today.

Combs’ second priority was highways. The Federal

Highway Program, the

interstate system, was well-under way when Combs became governor. So he

“hit the ground running,’ again. As the interstates’ construction was

moving north and south through Kentucky, Combs was determined that

Kentucky would not embarrass itself because of traffic bottlenecks due

to unfinished four lanes. Kentucky was actually ahead of other states in

building these highways. Combs felt that we also needed four lanes

traveling the state east and west. So during his term he finished the

Western Kentucky Turnpike and the Mountain Parkway in the east. Before

he left office the Bluegrass Parkway was well on its way into central

Kentucky.

The Mountain Parkway was most dear to his heart though.

Eight years

after Combs left office Governor Louie Nunn honored Combs by officially

naming the two ribbons of concrete the Bert T. Combs Mountain Parkway.

During Bert T. Combs’ term as governor of Kentucky (1959-63) his top priorities were education and roads. He started the Community College System and Kentucky Educational Television (KET) that both serve our citizens so well today. The Mountain Parkway, which runs through Clark, Powell, Wolfe, and Magoffin counties, was most dear to Governor Combs. Eight years after he left office the Bert T. Combs Mountain Parkway was named in his honor. In the photo above the Governor, left, visits with citizens of Powell County in Stanton, Kentucky, in 1979. Pictured are: John Brewer, with back to camera; Shelby Martin, wearing hat; Floyd Anderson; and Reba McQueen. (Photo courtesy of Floyd Anderson, 70 Allen Drive, Stanton, KY 40380.)

Before he was elected governor Combs met many times with Bill May, a

highway engineer from Pikeville, and discussed both their dream of

building a highway for the Eastern Kentucky mountain people. The highway

was being designed before the election. There was a rumor that May asked

Combs how they would get paid? Supposedly Combs told him, ‘You won’t if

I don’t get elected governor.’

The Mountain Parkway was known

as a developmental highway: One of the

first in the country. Generally, existing traffic flow has to be great

enough to justify the financing of a new highway. That kind of traffic

flow between the mountains and the Bluegrass didn’t exist. Combs,

undaunted, convinced the powers that if Kentucky would build the

Mountain Parkway the mountain people would drive to the Bluegrass to

shop and do business, and the central Kentucky people will visit the

mountains. Combs and his financial staff had to meet with six different

financial institutions in New York before they found one that would help

Kentucky build the Mountain Parkway. The tolls paid for the highway

ahead of schedule, and the toll plazas were removed in 1985.

During the Mountain Parkway dedication at the Campton interchange on

May 8, 1963, Combs said, “This highway, with its extensions, will reveal

to our visitors some of the most beautiful scenery in America, the

southern Appalachian Mountains. And the visitors will come, legions of

them, now that the barriers of isolation have been pierced by these

rapiers of concrete. They will come to behold the grandeur of the hills

and to enjoy the hospitality of the mountain people.

“We hereby dedicate the Mountain Parkway as a lasting symbol of the

perseverance and hopes of the mountain people and to the continued

progress and well-being of all the people of our Commonwealth.”

In reading through the Bert T. Combs papers I have found several

places where he had told someone, “I would like to leave some sort of

track, showing that I’ve been here.” And tracks did he leave for all

Kentuckians, but especially for his mountain people.

Another one of his projects of the heart was the Kentucky State Parks

system. Bert believed that with the natural beauty so prevalent in

Kentucky, the rich history, and the hospitality of the state’s people,

we could become a destination for millions more tourists each year. He

believed that the parks could build resort hotel accommodations that

were comfortable and hospitable, yet affordable to the American family.

So with monies appropriated he changed a park system that was mostly

campgrounds into resorts. He enjoyed visiting the parks after some of

the hotels were built. He took great pride in what they would do for the

economies of each community where they were located. His visits were

somewhat like an inspection.

He visited one particular park.

The trees were awesome driving into

the entrance. The creek was clean. The hotel was just what he expected.

Inside the lobby was beautiful with the wooden floors and the massive

stone fireplace. He sat down in the dining room, admiring the furniture,

the rustic chandeliers, the table linens, and the view outside

overlooking a mountain valley. Then the waitress walked over to his

table. She had a toothpick sticking out the side of her mouth and asked,

“Whatcha ont?’

I guess he figured he couldn’t get everything perfect.

Combs felt that if he was with his people he could better listen and

learn what the people expected out of their government. He took the

office of the governor to the people 41 times, the only political

project of its kind in the United States. Combs and his staff actually

set up shop in 41 different locations and invited the people to come in

and tell them what was on their minds and suggest possible solutions.

The staff didn’t completely enjoy the experience but Combs knew it was

important. He was at his best with the people.

Out of these

meetings came the idea of over 1,000 litter barrels

marked and placed along Kentucky highways. Ponies and saddles were

bought for orphans, rowboats for the boys’ camp near Kentucky Dam, and

coloring books for the mentally impaired. He moved the Derby breakfast,

which had been for the governor’s cronies in the mansion, to tents on

the lawn, and everyone was invited. The Derby breakfast is still done

the Combs way.

He built amphitheatres in some of the parks and

encouraged live dramas. He even encouraged his pretty teenage daughter, Lois, to work as

a waitress at Cumberland Falls State Park and Kentucky Dam.

Once a year he invited journalists from all over the state to meet

with him and his staff in Frankfort. They were to ask any questions they

wanted, and they would be answered objectively.

Combs was

ridiculed harshly for building the floral clock between the

Capitol and the Annex. Even some of his own people advised him not to

build it. They said it would be a political nightmare. The clock turned

out to be one of the most popular tourist attractions in Frankfort and

still is after 43 years.

Combs’ executive order banning

discrimination may have come out of

one of the 41 meetings. It also may have come from the idea that Combs,

being a mountain man, knew what it meant to be a member of a minority

group. He polled the House and Senate to see if a law could be passed to

end discrimination. When he knew that was not possible he signed an

executive order to end discrimination. He had often said that, “An end

to segregation is coming and that those who fight it are only spreading

bitterness.”

President Kennedy wrote Combs a personal letter thanking him for

stepping forward and doing what was right. The subject weighed heavily

on Combs’ thinking. In March 1963 Combs addressed the Conference for

Brotherhood in Chicago.

He spoke, “Equality and cooperation

are the lamps of civilization. As

civilized people, then, we Americans must accept the challenge and lead

the way by lighting the torch of freedom for oppressed people, both at

home and all over the world.

“The whole universe knows

first-handed that while America attempts to

provide food, comforts, and protection for most of the distant people of

the world, it still refuses to provide here at home the most vital of

all constitutional rights, first class citizenship for everyone. But the

time has come when the opponents of decency and right must recognize the

inevitability of change.

“At the beginning of our great

nation Americans assumed a mortgage on

their freedom, but after almost two centuries we are in the throes of

bankruptcy, because we are behind on our payments to the United State

Constitution.

“In this day and time, freedom has become more

than an academic word.

It is no longer sufficient merely to talk and write of the ingredients

of the good life and the dignity of man. In this grave hour in which you

and I are privileged to live, fraught periodically with great pride and

great promise, the value and durability of full citizenship rights are

to be found more in our actions than our words, in our collective

efforts and individuals beliefs.”

Writer’s Note:

Bert T. Combs’ last chapter and shining hour was yet

to come. Check out the September issue of The Kentucky Explorer to find

out more about Bert Combs’ contribution to our society. Also, watch for

some exciting news regarding an event concerning Bert Combs that will be

happening this year.

Editor’s Note: In the July-August 2004 issue of The Kentucky Explorer Joe Bowen shared the first part of a two-part series of Bert T. Combs’ progressive administration as governor of Kentucky. Combs’ top priorities for the state were education and highways. For most of the residents in Eastern Kentucky, Combs became an icon, and was considered a governor of the working class people.

Now, Joe Bowen of Taylorsville, Kentucky, continues with part two of his story with exciting news.

Part II

Governor Combs To Be Honored With Memorial In Powell County

Fern Hill On Cane Creek Was The Beginning Of A More Relaxing Time For The Governor

By Joe Bowen - 2004

In the first article about Bert T. Combs I ended with, “Combs’

shining hour was yet to come.” But before that shining hour Combs had

heartaches like most of us.

In 1954 U. S. Senator Earl

Clements and Governor Lawrence Wetherby

decided that Combs could be the man to become Governor of Kentucky and

unite the Democrat party that Happy Chandler was splitting into

factions. One night they called Combs to the Governor’s Mansion to

discuss the possibility. Combs told them that he couldn’t see himself as

governor. He also told them that he had a little boy who was handicapped

and didn’t want anything to interfere with his son’s happiness.

In an interview with George W. Robinson (Bert T. Combs, An Oral

History), Governor Lawrence Wetherby said that Combs had problems over

the boy. Wetherby said they continued to talk about Combs running for

governor and he would come back to the boy. “Well,” Combs said, “I’m

just a little reluctant because of the fact you get into a campaign and

people will talk about it.” Combs was also worried about how Tommy would

be cared for. Maybe a little aggravated, Wetherby finally told Combs,

“You can do a lot more for him as governor than you can by not being

governor.”

Combs was finally convinced and agreed to run.

(He lost in 1955 to A.

B. “Happy” Chandler, but ran again in 1959 and won.) Tommy stayed a

major part of Combs’ life to the end. Combs had birthday gatherings in

honor of Tommy late in life, while living at his farm, Fern Hill, in

Powell County.

Combs worked hard as governor, introducing

184 new and worthwhile

programs in Kentucky. It was extremely important to Combs that the

person who followed him into the governor’s office would continue those

programs. So he backed Ned Breathitt for governor. Breathitt had helped

Combs during his governorship. Breathitt won and the election cycle for

the 1967 governor’s race was coming up and a lot of people wanted Combs

to run again. They were sure he would win because he and Breathitt had

grown so popular. Combs followers knew that the successes of the state

government of the past eight years could go on for at least four more.

Combs agreed at first to run, but at the last minute changed his mind.

When asked why he didn’t run, Combs replied, “By reason of my family

situation, personal problems, and my age. I decided I wanted to go with

the court.”

Governor Combs’ wife, the former Mable Hall, a mountain woman

herself, didn’t want Combs to run again. So he didn’t. A short time

after that, in 1969, Bert and Mrs. Combs divorced.

In January 1967 Combs was nominated to serve on the Federal Court of

Appeals. In April, Combs was endorsed by the United States Senate

Judiciary Committee and confirmed by the United States Senate as Federal

Appeals Judge of the Sixth Circuit. The Courier-Journal reported that

this judgeship removed Combs from Kentucky politics and that he was one

of the “most colorful, popular, and respected figures in Kentucky.” He

would serve in Cincinnati, removing him from the political action of

Kentucky that he so enjoyed.

Later Combs said the

“Federal Appeals Court is somewhat isolated.” In

Robinson’s oral history, Tommy Carroll said, “Combs quickly became a

very lonely man in Cincinnati. He was miserable in that position.”

Many people thought that Combs resigned the court to run for governor

in 1971. Combs later said that a long-time friend, John Tarrant, had

encouraged him on several occasions to come into his law firm as a

partner, which he did.

Friends across the state had encouraged

him to run for governor in

1967 and 1971. His second wife, Helen Rechtin, from Louisville, was also

encouraging him in 1971. He ran for governor in 1971, and to the dismay

of thousands lost to Wendell Ford.

That series of events,

not running for governor in 1967, the divorce

from Mable Hall, always worrying about his son’s (Tommy) well being,

sitting in a lonely seat of the U. S. Court of Appeals, losing the 1971

election, and then a second divorce, were major bumps in the road to a

great Kentuckian. But things would get better.

He settled in as senior partner of Wyatt, Tarrant, and Combs Law

Firm; the largest in Kentucky.

Bert T. Combs hired Sara Walter as an assistant in his law firm in 1979.The couple was married December 30, 1988. The ceremony was held at Fern Hill, the beautiful farm and log home where the couple resided, in Powell County. (Photo courtesy of Sara Walter Combs.)

In 1979 Combs hired an assistant lawyer, Sara Walter, to help with

his workload in the law firm. Their mutual admiration developed into a

deep and abiding love. Combs had bought a farm in Powell County on Cane

Creek. He wanted to live in the mountains close to his grandchildren in

Knott County yet have a comfortable drive to his Lexington law office.

Combs assigned Sara the job of building him a home on Cane Creek. She

immersed herself in the project and became the construction manager and

assistant to the architect. After a year the result was an elegant, log

home nestled at the foot of a mountain overlooking Cane Creek and its

lush, green valley.

Sara named the farm and home Fern Hill after a poem written by Dylan

Thomas. To Combs the poem described Fern Hill and what it was and what

it would become. Sara Walter Combs told The Clay City Times in 1992 that

Fern Hill was “time-out from time itself for the judge.”

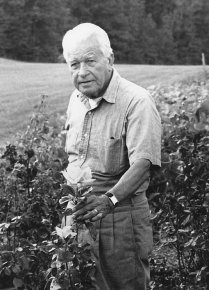

Governor Bert T. Combs stands in his beautiful rose garden, about 1989, at Fern Hill in Powell County. Combs worked hard as Kentucky’s governor. He introduced 184 new and worthwhile programs during his administration. (Photo by Tim Webb, Richmond, KY)

There, with Fern Hill, the Lexington office, and Sara Walter at his

side, Combs was the legal council for 66 of Kentucky’s poorest school

districts, without financial compensation. They sued the governor of

Kentucky and the General Assembly claiming the Kentucky educational

system was unconstitutional.

The representatives of these

66 school districts convinced Combs,

according to Combs’ article in the Harvard Journal on legislation, that

Combs, “at one time claimed to be Kentucky’s education governor.” They

also reminded Combs that he “was now holding himself out as a top-notch

lawyer.” Combs agreed on both accounts.

In the Harvard

article Combs said, “they also reminded me that

Kentucky’s General Assembly had never (at least within the memory of any

living person) adequately financed the state’s public schools. The

results, according to them, was that the children of Kentucky were being

deprived of their constitutional right to a decent and equal education,

and that we as onlookers were wasting our “seed corn” for the future.”

Sara Walter, Combs’ closest confidant and legal assistant, worked on

the lawsuit with Combs for months and months, preparing it to be

presented to the court. She also helped Combs write the very

enlightening and, at the end, humorous article for the Harvard Journal.

The suit was filed in 1985. According to the Harvard account the

courts determined Kentucky’s elementary and secondary system was

inadequate and inefficient, the opportunity to obtain an adequate

education is a fundamental right protected by the Kentucky Constitution,

and the wide disparity in funding between the affluent districts and the

poor districts was discriminating to the children in the poor districts;

violating the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment to the

United States Constitution and Section 183 of the Kentucky Constitution.

The court’s decision was taken to the State Supreme Court, where the

lower court’s decision stood. Because of this suit and the court’s

decision, we have the Kentucky School Reform Law.

This law completely changed Kentucky’s educational system for the

better.

I would recommend that anyone interested in education in Kentucky

read Combs’ article in the Harvard Journal on Legislation, Vol. 28, No.

2, dated Summer 1991, and those interested in Combs should read

Robinson’s oral history mentioned above.

Shortly after the

oral argument in the Supreme Court, Bert and Sara

were married on December 30, 1988, at their log home, Fern Hill, in

Powell County.

In several articles the Courier-Journal

and the Lexington Herald

quoted Combs as saying that as a student, he attended schools “that had

no library, no laboratory, a very sketchy curriculum, poorly paid

teachers, inadequate buildings, all the rest; and I am very conscious of

the fact that it has been a handicap to me through my whole life.”

I couldn’t imagine Bert Combs, the great man that he was, feeling

inadequate. I asked Sara Combs, who is now Chief Judge of the Kentucky

Court of Appeals, if this Combs statement was accurate. She assured me

that he lived with the thought his entire life.

The move to

Fern Hill was the beginning of a more relaxing time for

Bert Combs. He was still practicing law in Lexington, enjoying Fern

Hill, and doing light farming.

Then tragedy struck.

It was December 3, 1991, cold and rainy. Combs

called his wife, Sara, from Lexington and told her he would be a little

late getting home. Darkness fell, the river was rising, and he had not

arrived home. A worried Sara began calling friends and neighbors. No one

had seen or heard from him since he left his office in Lexington. Those

in Lexington knew he was headed home. Soon hundreds of people were

hunting for Combs.

Bert Combs’ route home took him off

the Bert T. Combs Mountain

Parkway at Stanton; onto Highway 15, a drive of three miles; then a left

at Rosslyn, on his way to Cane Creek. At Rosslyn he would drive across

the lane which crossed Red River. On that dark night, due to heavy rain,

the Red River was flooding the road near the bridge.

Most of us in the valley, when we see the water rising over the road

at Rosslyn, we stop and decide, “Yes it’s safe to cross, or no it’s too

deep.” We all do it and several times each year someone has to be

rescued from their vehicle.

While everyone was looking

for Combs that night they wouldn’t utter

the possibility that most were thinking.

After daybreak

his car was spotted partially submerged, but Combs

wasn’t in the car. His body was found one-quarter-of-a-mile down the

river. Rob Matthews, Stanton Chief of Police was one of those who found

him. I asked Rob, “Did he drown?” He answered, “No, he had gotten out of

the car, got his coat and shoes off, and probably was swimming.” Rob

continued, “I found him out of the water, and that 80-year-old man was

still holding on to a two-inch tree.” Hypothermia had taken the life of

this tough mountain man.

After Bert Combs’ funeral the

Courier-Journal reported, “Bert Combs

was no saint.” John Ed Pearce, a long- time friend of the former

governor reminded the mourners with good humor, “He was a man in all

that word connotes. A man who loved good books, good talk, and good

stories. A man who loved deeply.”

After part one of this

article appeared in The Kentucky Explorer I

received a letter from David L. Jackson of Frankfort. Mr. Jackson, at one time, was president of Oneida Institute, and

his wife was a distant cousin of Governor Combs. One year Combs was

their commencement speaker. Mr. Jackson wrote Combs a thank you letter

and told him, “because I was married to a Combs, perhaps, I was

prejudiced, but, I thought you were the best governor that Kentucky ever

had.”

Jackson said he received a reply a few days later. It simply read,

“You should be prejudiced,” signed, Bert T. Combs.

In Robinson’s oral history, Wendell Butler, former state

superintendent, told the story on the campaign trail when Combs met a

man and asked for his vote. The man said, “Judge, I wouldn’t vote for

you if you were Saint Peter.” Combs shot back, “You couldn’t vote for

me. You wouldn’t be in my district.”

While Combs held

the office of governor he became a beekeeper. He

cared for five stands of bees on the mansion grounds. When he left

office and set up residence in Lexington he took the bees with him. The

bees began to fail in producing honey. To a friend he commented, “I

sorta expect that my queen bee has taken up with a horse fly.”

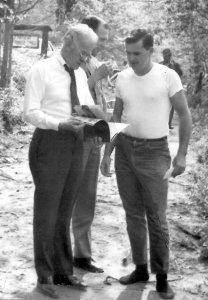

Joe Bowen, right, met Governor Bert T. Combs at the Red River Gorge in 1971. Governor Combs asked Bowen not to leave Powell County, for he was needed there, but he did leave for 31 years. Bowen is planning to move back to Powell County within the next year and plans to help the people however God sees fit. (Photo courtesy of Joe Bowen.)

Joe Bowen, P. O. Box 425, Stanton, KY, 40380, shares this article with our readers.

Powell County native, Joe Bowen, originated the idea for the Bert T. Combs statue and is the primary driving force behind the project. Joe was also instrumental in the Woody Stephens statue that now stands at the Powell County Courthouse.